Designing for Sound: An Acoustical Adventure

“I can’t hear the dialog! Why can’t I hear the dialog?”

This is a question that I am asked sometimes while mixing in theme park attractions, whether it’s a dark ride, exhibit or any other less than pristine environment. Is it a bad recording, bad sound mixing or something else altogether?

Some of the best theme park attractions are driven by great storytelling. Since dialog is such an integral part of telling that story, what happens when the audience can only hear half of what is being said? It’s just not going to be an effective attraction, and both the guests and owners will be disappointed. In many of these special venue environments, there are so many variables to deal with, but most often, the problem is acoustics.

Music and sound effects can be a little more forgiving to the ear of the general audience because you can still get pretty good energy and emotion from a piece of music, even if it’s bouncing around the room too much. But when you have dialog bouncing around too, it becomes a jumbled unintelligible mess.

Now I’m not an acoustical engineer, but all sound designers and sound mixers must know enough about sound absorption, frequencies and reflections to be able to recommend solutions to fix the problems that often arise. But sometimes acoustics is considered an expense that doesn’t really add that much value.

Although we don’t design or spec acoustics for our attractions, our designers and engineers at Falcon’s are sensitive to the importance of acoustical treatment, and that has made a huge difference in many of our recent attractions.

In general, it’s quite easy and inexpensive to add acoustical treatment to ceilings and walls while in the earlier stages of construction. Adding acoustics later is very time consuming, messy, disruptive, and much more costly. So, when we are able to suggest that acoustics be implemented early on in the process, it makes a world of difference.

Audio clip from Queens Of Egypt Exhibition by National Geographic Society.

One notable example that our design team was able to help with greatly, was the National Geographic Museum in Washington DC. One of the main attractions in the museum is a 3D immersive theater with 7.1 surround sound. This theater was home to some amazing productions created by our media team, such as “The Tomb of Christ”, later followed by “Queens of Egypt”.

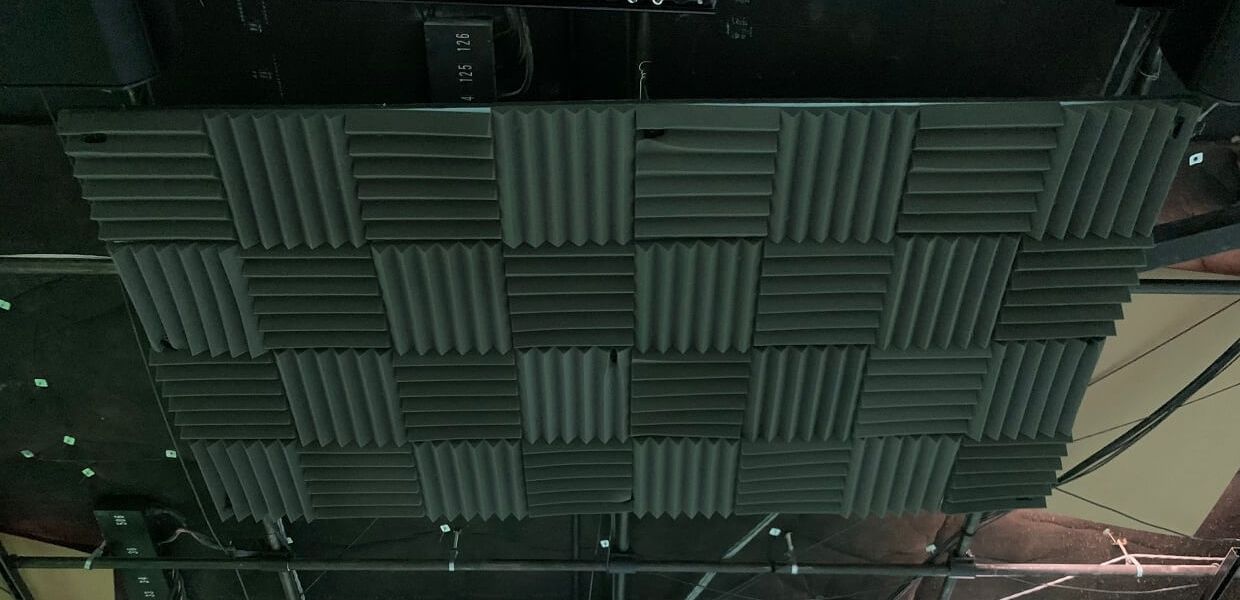

The room started out with a bare ceiling, concrete floor and a solid projection screen that enveloped the guests in a horseshoe shape. This meant that sound would be bouncing off several huge hard surfaces, which would have created a dialog nightmare. Carpeting was out of the question because the floor was also a projection surface. The screen itself can’t be treated, so the main area that was open to work with was the ceiling. The solution was to hang what are called acoustical clouds, which are panels hung by cables from the high ceiling and treated with black acoustical foam which basically goes unseen by the guests.

Taking care of acoustics in the ceiling makes a substantial difference, even when the other surfaces can’t be touched. The team however was able to add some treatment to the walls above the screen which was quite helpful as well.

So how does this type of foam treatment work? It takes just a small bit of science to help explain. The acoustical treatment must be thick enough to absorb the problematic sound waves and keep them from bouncing back at you. The lowest frequency in our hearing range is 20 hertz. Would you believe the length of that sound wave is about 54 feet long?

Think of it as a 54-foot-wide and 30-foot-high sea swell in the middle of the ocean. That’s the size of the wave that travels unseen through the air. Compare that to 20,000 Hertz, the highest perceptible frequency which has a wavelength of just over 1/2 inch. The human voice is in the mid to upper part of that range.

Those huge low frequency waves are pretty much impossible to absorb, but the human vocal range is very achievable. Without getting too deep into the math of it all, the basic rule of thumb is called the quarter rule. This just means that if your foam is a least as thick as 1/4 of the length of the sound waves that are causing the biggest problems, then you’re in pretty good shape. 3-4 inches of acoustic thickness will take care of most of the havoc created by dialog in an attraction, and at the same time, the music and effects will be considerably better sounding. But I’m happy when I can get an inch or two of treatment.

Acoustics are sometimes not valued as much as choosing great speakers and having a good design for placement. But when all three of these things are taken into consideration, we have the foundation to create an amazing sound mix.